doi: 10.56294/cid202237

ORIGINAL

Community intervention on oral cancer in high risk patients

Intervención comunitaria sobre cáncer bucal en pacientes de alto riesgo

Rosa

María Montano-Silva1

![]() *, Yanelilian

Padín-Gámez2

*, Yanelilian

Padín-Gámez2 ![]() *, Yoneisy

Abraham-Millán1

*, Yoneisy

Abraham-Millán1 ![]() *, Reynier Ruiz-Salazar3

*, Reynier Ruiz-Salazar3

![]() ,

Ladisleny Leyva-Samuel1

,

Ladisleny Leyva-Samuel1 ![]() , Douglas

Crispín-Rodríguez4

, Douglas

Crispín-Rodríguez4 ![]()

1Facultad de Ciencias Médicas Isla de la Juventud. Isla de la Juventud, Cuba.

2Facultad de Ciencias Médicas Isla de la Juventud. Clínica Estomatológica Docente Dr. José Lázaro Fonseca López del Castillo. Isla de la Juventud, Cuba.

3Facultad de Ciencias Médicas Isla de la Juventud. Hospital General Docente ¨Héroes del Baire¨. Isla de la Juventud, Cuba.

4Facultad de Ciencias Médicas Isla de la Juventud. Policlínico Docente Universitario Orestes Falls Oñate. Isla de la Juventud, Cuba.

Cite as: Montano-Silva RM, Padín-Gámez Y, Abraham-Millán Y, Ruiz-Salazar R, Leyva-Samuel L, Crispín-Rodríguez D. Community intervention on oral cancer in high risk patients. Community and Interculturality in Dialogue 2022; 2:37. https://doi.org/10.56294/cid202237

Submitted: 24-08-2022 Revised: 01-11-2022 Accepted: 11-12-2022 Published: 12-12-2022

Editor:

Prof. Dr. Javier González Argote ![]()

ABSTRACT

Introduction: oropharyngeal cancer mortality ranked tenth among cancers in Cuba in 2020 and 2021.

Objective: to implement a community intervention on oral cancer in high-risk patients aged 35 to 59 years.

Method: a community intervention with quasi-experimental design, before-after type with control group, was carried out in clinics 7, 25 and 27 of the polyclinics of Nueva Gerona, Isla de la Juventud between January and September 2022. A sample of 454 patients was selected, distributed in a control and experimental group for each clinic, formed by the same number of patients at random. Theoretical, empirical and mathematical-statistical methods were used and the variables used were: risk for predicting oral cancer, risk factors, level of knowledge about oral cancer and teaching methods.

Results: the risk of developing oral cancer was high in 69 % of the patients between 35-59 years of age in the clinics under study. Before the intervention, a poor level of knowledge predominated, representing 57,7 % of the experimental group. After the intervention, 86,8 % of the main risk factors initially identified decreased.

Conclusions: the use of new information and communication technologies in promotion and prevention activities contributed to raise the level of knowledge about oral cancer, the main risk factors associated to its appearance and oral self-examination, allowing to transform the modes of action and to evaluate as satisfactory the community intervention implemented in high-risk patients between 35-59 years old.

Keywords: Oral Cancer; Risk Factors; Oral Self-examination; Health Promotion; Oral Cancer Prevention.

RESUMEN

Introducción: la mortalidad por cáncer orofaríngeo ocupó el décimo lugar entre los tipos de cáncer en Cuba en 2020 y 2021.

Objetivo: implementar una intervención comunitaria sobre cáncer bucal en pacientes de alto riesgo con edades entre los 35 y 59 años.

Método: se realizó una intervención comunitaria con diseño cuasi-experimental, tipo antes-después con grupo de control, en los consultorios 7, 25 y 27 de los policlínicos de Nueva Gerona, Isla de la Juventud entre enero y septiembre de 2022. Se seleccionó una muestra de 454 pacientes distribuidos en un grupo de control y experimento para cada consultorio conformados por la misma cantidad de pacientes al azar. Se utilizaron métodos teóricos, empíricos y matemáticos-estadísticos y las variables: riesgo para predecir cáncer bucal, factores de riesgo, nivel de conocimiento sobre cáncer bucal y medios de enseñanza.

Resultados: el riesgo a padecer cáncer bucal fue alto en el 69 % de los pacientes entre 35-59 años de los consultorios en estudio. Antes de la intervención predominó un nivel de conocimiento malo representando el 57,7 % del grupo experimental, logrando elevarlo a bueno después de la misma en un 86,8 % disminuyendo los principales factores de riesgo identificados inicialmente.

Conclusiones: el uso de las nuevas tecnologías de la información y las comunicaciones en las actividades de promoción y prevención contribuyó a elevar el nivel de conocimiento sobre cáncer bucal, los principales factores de riesgo asociados a su aparición y el autoexamen bucal, permitiendo transformar los modos de actuación y evaluar como satisfactoria la intervención comunitaria implementada en pacientes de alto riesgo entre 35-59 años.

Palabras clave: Cáncer Bucal; Factores de Riesgo; Autoexamen Bucal; Promoción de Salud; Prevención de Cáncer Bucal.

INTRODUCTION

In the American Cancer Society Manual(1), cancer is defined as a neoplastic process of polycellular and local tissue origin characterized by cytological dedifferentiation and autonomy from local and general homeostasis. Additionally, it exhibits properties of infiltration with cytolytic effects on neighboring normal tissue and the capability to metastasize to other regions of the body.

Oral cancer ranks among the top ten locations for cancer incidence worldwide, including in Cuba(1), representing a significant health concern affecting a considerable group of individuals. It stands as one of the most impactful diseases in a person’s life, leading to permanent consequences that have psychological effects and repercussions on the patient’s social and family environment.

Every year, 9 000 000 people worldwide receive a cancer diagnosis, with approximately 5 000 000 succumbing to the disease. Current estimates indicate that there are around 14 million individuals living with cancer. Among all types of cancer, oral cancer stands as the sixth most common cause of death globally. Every year, there are 20 000 to 25 000 new cases reported worldwide, resulting in between 13 000 and 14 000 patient deaths. (2)

In Cuba, oral cancer is a noteworthy concern, accounting for four to seven out of every 100 reported cancer cases.(3) According to the Statistical Health Yearbook of Cuba, the mortality data for lip, oral cavity, and pharyngeal cancer in recent years is as follows: 829 deaths in 2017;(4) 826 deaths in 2018;(4) 893 deaths in 2019;(6) and 905 deaths in 2020;(7) with a higher predominance among individuals over 60 years of age and males. In Isla de la Juventud, there were 8 positive cases and 2 deaths in 2017;(4) in 2018, eight and five, respectively;(5) and four and five in 2019.(6)

In 2021, 57 male patients aged 30 to 44 years were reported to have been diagnosed with cancer in the lips, oral cavity, and pharynx, with an incidence rate of 5,1 per 100 000 males. In the 45-59 age group, there were 551 patients, yielding an incidence rate of 41,2 per 100 000 males and no cases were reported in females. During the same year, a total of 899 deceases were recorded, resulting in a mortality rate of 8 per 100 000 inhabitants. Among males, there were 689 deceases, translating to a mortality rate of 12,4 per 100 000 men, while among females there were 210 deaths, with a mortality rate of 3,7 per 100 000 females. The most affected age group in both sexes was 60-79 years, with 354 deaths in males, constituting a rate of 39,9 %, and 108 deaths in females, reflecting a rate of 10,9 %. This underscores the need for the implementation of preventive efforts from early ages to age with a good quality of life.

Despite the implementation of the Early Detection Program For oral cancer, the incidence of this pathology continues to rise annually. Current morbidity and mortality patterns are intricately linked to human behaviors and lifestyles. Health Education is a powerful tool for professional work in Primary Health Care. The analysis of these circumstances led to the formulation of the following scientific problem: How can we contribute to preventing the occurrence of oral cancer in high-risk patients of clinics 7, 25, 27 in Nueva Gerona in 2022? The results of the ongoing research present a study on the impact of information and communication technologies on promotion and prevention activities for oral cancer in high-risk patients aged 35-39 years. The scientific novelty lies in the proposal of educational multimedia, a website, and a mobile application to elevate the population’s level of knowledge about oral cancer, its primary risk factors, and oral self-examination. The current investigation contributes to strengthening the collective effort to preserve social achievements in health, education, and the informatization of Cuban society. The objective is to implement a community intervention on oral cancer in high-risk patients aged 35-59 years from clinics 7, 25, and 27 in Nueva Gerona in the year 2022.

METHODS

A community intervention with quasi-experimental design, before-after type with a control group was conducted in clinics 7, 25 and 27 of the University Teaching Polyclinics “Juan Manuel Páez Inchausti” and the Stomatology Clinic Dr. José Lázaro Fonseca López del Castillo, respectively, from January to September 2022.

Population and sample

The population consisted of 658 patients aged 35-39 years from the three medical offices under study: 274 from clinic 7, 196 from clinic 25 and 188 from clinic 27. The sample comprised 454 high-risk patients for oral cancer, distributed across the three clinics. The sampling method employed was probabilistic, simple random, and was composed as follows: 210 patients from clinic 7, 122 from clinic 25, and 122 from clinic 27. From this sample, both an experimental group and a control one were determined within each clinic.

The selection of the clinics was conducted utilizing the raffle procedure, while for the units of analysis in each group of the experiment, the systematic selection procedure of sample elements was employed. This was executed based on an interval (K); hence, from the total number of patients in the sample (N), the number of patients forming the groups is (n), and the interval will be (K). Accordingly, K=N/n where (N) is the total number of patients, (n) is the sample for each group of the experiment, and (K) is a systematic selection interval. The process commenced randomly with the use of a die, and based on the number obtained when rolling it, the initial selection was made from a list prepared for this matter. The sample was divided into two groups, one control and one experimental, in each clinic. A random assignment of patients to each group in each office was done using an unbiased coin.

Inclusion criteria

Patients aged between 35 and 39 years old, with whom the educational-preventive work could be conducted and who provided their consent.

Variables

Dependent variables: risk of predicting oral cancer, risk factors associated with the onset of oral cancer, level of knowledge on oral cancer.

Independent variables: means of teaching (multimedia, website, mobile application).

Techniques and procedures

Bibliographic searches on the study topic were conducted in both national and international texts, encompassing both digital and hard-copy formats. The sources of information used during the research included: Interview Form to predict the risk scale and the Survey of Knowledge about oral cancer for individuals aged 15 years and older.

With the prior informed consent of the patients, a form was administered to assess the risk of developing oral cancer, thereby constituting the study sample comprised of patients identified as having a high risk of suffering oral cancer. A survey on the level of knowledge about oral cancer was conducted for all patients in the sample, both before and after the community intervention. The survey consists of 10 questions, and the total evaluation is scored out of 24 points, categorized as good (17 to 24 correct answers), fair (9 to 16 correct answers) or poor (less than 9 correct answers). Both the form and the survey were applied to the study sample before and after the community intervention.

Oral hygiene was assessed quantitatively before and after the intervention during dental consultations using the Love Index for dentate patients. This index categorizes hygiene as either efficient (less than 20), or deficient (20 and above). For completely edentulous patients, the presence or absence of dental bacterial plaque or calculus, along with the condition of the prostheses were visually evaluated.

![]()

Educational multimedia, a website and a mobile application on topics related to the promotion and prevention of oral cancer were designed and utilized in the experimental group for six months with a weekly frequency, enabling the measurement of their impact. These tools were not applied in the control group. The website was implemented in the clinic 7, the multimedia in the clinic 25, and the mobile application in the clinic 27, serving as teaching aids.

The multimedia was developed using Mediator Software, and Photoshop 8.0 also was utilized for image editing, with a disk space requirement of 10 megabytes. The website was created using the Auto Play Media Studio 10 Trial program and has a size of 480 MB = 491520KB. The mobile application, in its version 1.0.0 was named “OdonClass”. The application was developed using the Andromo website, which facilitates the creation of free applications. It is a simple, user-friendly application with a file size of 45,04 MB.

These teaching methods contain: concepts, risk factors, signs and symptoms, preventive measures, oral self-examination, image gallery, video gallery, and self-assessment, aiming to foster interactivity with the user. The design of each linked page was created through a central page, which directly influences the directory tree structure. Access to these resources is possible through both computers or mobile devices.

Data processing and analysis techniques

The collected data were systematically organized into a database. The results were visually presented through graphs. A computer equipped with Windows 10 operating system and Microsoft Word and Excel programs were utilized for text and graph creation. The data were processed by calculating absolute frequencies, relative frequencies, and percentages. Chi-square was calculated using the following equation:

![]()

x²= Chi-square

Oi= observed value

Ei= expected value

Ethical Considerations

The data obtained in the study were treated as confidential, demonstrating respect for the principle of autonomy outlined in the international code of bioethics for interventions in human beings. Informed consent was obtained from the patients who participated in the intervention.

RESULTS

In the three clinics under study, a high risk for oral cancer predominated in more than 62 % of the population aged 35-59 years old. Among the 658 patients comprising the population, 454 were identified as high risk, constituting 68,997 % (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of the population according to the risk of predicting oral cancer in the studied clinics

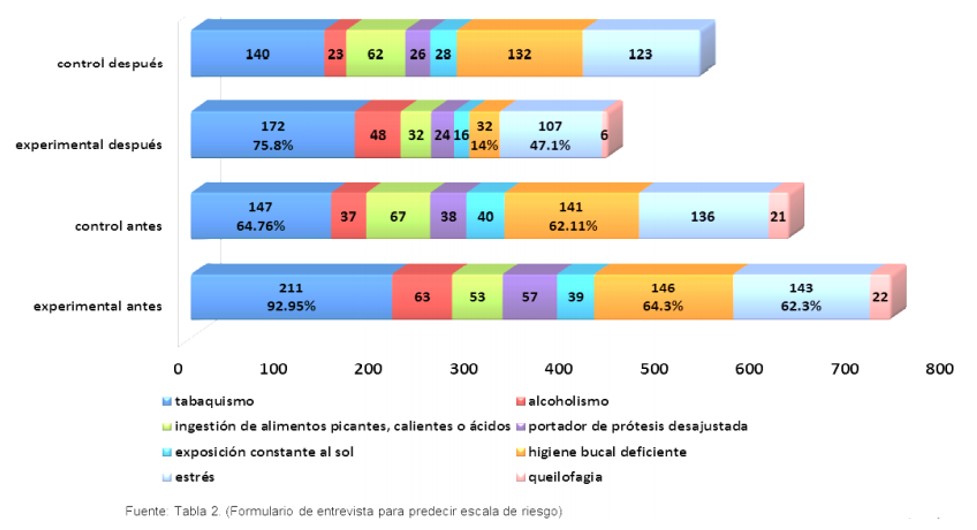

In both groups of the experiment, the main risk factors were identified as smoking, poor oral hygiene, and stress. Following the implementation of the intervention, a reduction in all factors, especially the three with the highest incidence, was observed in the experimental group by more than 20 % (figure 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of the sample according to risk factors in the study groups, before and after the community intervention

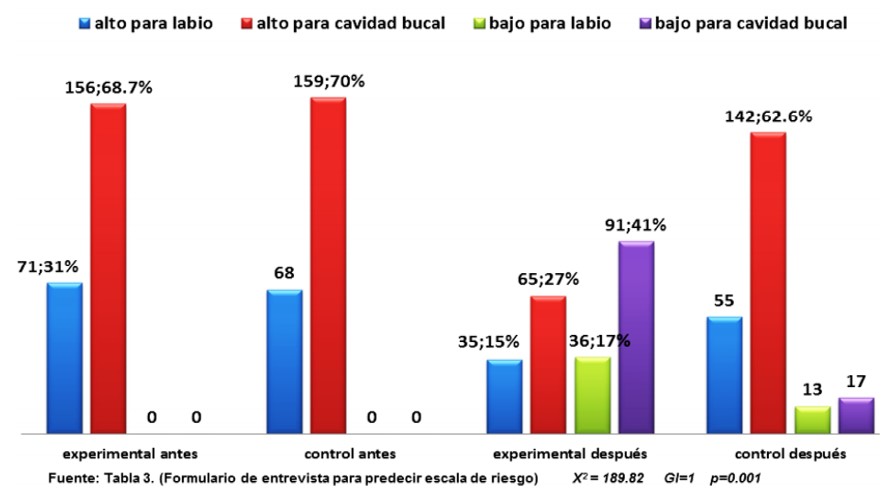

In both groups of the experiment, the risk of developing cancer in the oral cavity was higher than for lip cancer before the educational intervention, accounting for 68,7 % for the experimental group and 70 % for the control group. Following the community intervention, more than 76,1 % of patients in the experimental group successfully transitioned from high to low risk (figure 3).

Figure 3. Distribution of the sample according to the risk of predicting oral cancer in the lip or oral cavity of the study groups before and after the community intervention

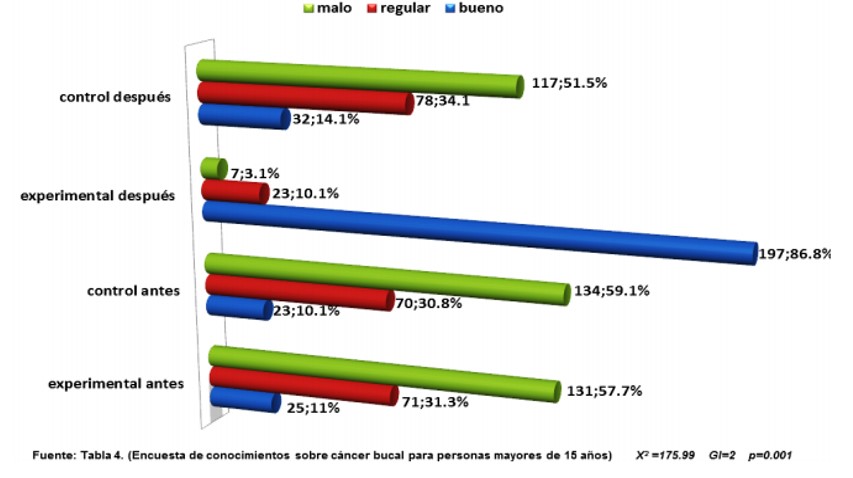

Before the community intervention, a poor level of knowledge predominated in the study groups, with 131 out of a total of 227 patients, representing 57,7 % in the experimental group and 134 patients in the control group, representing 59,1 %. After the intervention, a good level of knowledge became prevalent, with 197 patients in the experimental group, representing 86,8 %, and 117 patients with a poor level of knowledge in the control group, representing 51,5 %. Significant changes were observed after the intervention in the experimental group, elevating the level of knowledge to good in more than 85 % of patients, and only 7 patients remaining with a poor level of knowledge, accounting for 3,1 %; this was not the case in the control group (figure 4).

Figure 4. Distribution according to the level of knowledge in the study groups before and after the community intervention

DISCUSSION

The identification of patients at high-risk enabled the acquisition of the study sample. The Risk Scale for predicting oral cancer can gauge the probability that each individual has of developing oral carcinomas, and simultaneously, serves as a guide for educational and preventive efforts in patients.

The findings from several studies conducted in Cuba align in identifying smoking, poor oral hygiene, and stress as predominant risk factors associated with the occurrence of oral cancer: Marín (8), Olazabal (9), Salazar (10), Matos (11) y Hernández (12). Recognizing these risk factors have proven valuable in conducting health promotion activities effectively, aiding also in the organization of primary preventive measures, and highlighting the risk factors that require specific protection, both within the patient and in their family or community environment.

Similarities can be observed in the research carried out by Vásquez (13) where a high risk of developing oral cancer predominated due to the influence of several risk factors within its study population simultaneously. Considering that the modification of detrimental lifestyles to beneficial ones is deemed a challenge for stomatologists, the intervention can be qualified as satisfactory, as it reduced the risk by changing the modes of action in the experimental group. (14)

The presence of a cluster of risk factors associated with the onset of oral cancer is the cause of a heightened risk of developing this pathology. Consequently, the authors posit that if the individuals are cognizant of the probabilities of developing oral cancer, they could contribute individually to positive lifestyle changes within society, thereby, enhancing their own health and quality of life. Each patient would be aware of the risk factors influencing them, and at the same time, they will be able to perceive the risks for their family and community. Through this, since their individual protagonism, they can become community health promoters.

In the conducted research, some respondents were aware of the method and frequency of brushing but did not execute it correctly. More than half of the patients reported only visiting the stomatologist when they experienced discomfort or pain. The most significant deficiency identified by the authors was that patients did not identify the main risk factors associated with the onset of oral cancer, were unaware of its signs and symptoms, and lacked knowledge on how to perform oral self-examination.

In a study conducted in the United States (15), only 32 % of the population in Iowa demonstrated acceptable knowledge on the topic. In Peru, a questionnaire given to 150 dental students (16) concluded that only 38 % had a favorable level of knowledge. There is also agreement with research conducted in Habana, Cuba (16) where over 70 % of patients were assessed as having poor knowledge. Consistent outcomes were obtained in Nueva Gerona, Isla de la Juventud (10) where a predominance of poor level of knowledge was present before the intervention, and improvements were observed once the intervention was applied. However, differences were found in the study conducted in the same municipality but in La Fe (11), where a regular level of knowledge predominated.

Education of the community stands as the ideal method to elevate the level of knowledge and risk perception regarding oral cancer. Primary prevention should, first and foremost, motivate individuals, especially the young and adults, through compelling proposals that achieve massive and protagonistic participation of patients. This approach encourages them not to start the practice of unhealthy health habits; secondly, for those who already have the habit, the focus should be on motivating them to quit, and lastly, to modify or reduce those habits. (17,18) The didactic methodology directly influences an individual's motivation for change and affects the reception and assimilation of the message. It is crucial to emphasize that there are no standardized didactic techniques; they must be adapted to the objectives and the specific population group with which one wishes to work.

CONCLUSIONS

A high risk of developing oral cancer predominated in patients aged 35-39 years in clinics 7, 25, and 27 in Nueva Gerona in 2022.The main risk factors associated with the appearance of oral cancer in the studied sample were: smoking, poor oral hygiene, and stress. The utilization of new information and communication technologies in promotion and prevention activities contributed to elevating the level of knowledge about oral cancer, the main risk factors associated to its appearance, and oral self-examination. This, in turn, allowed for a transformation of modes of action, and the educational intervention implemented in high-risk patients between 35-59 years old was evaluated as satisfactory.

REFERENCES

1. Murphy GP, Lawrence W, Lenhard R. Oncología Clínica. Manual de la American Cancer Society. 2ª ed. Estados Unidos, 1996; 21(7).

2. Torres-Morales Y, Rodríguez-Martín O, Herrera-Paradelo R, Burgos-Reyes GJ, Mesa-Gómez R. Factores pronósticos del cáncer bucal. Revisión bibliográfica. Mediciego. 2016; 22(3).

3. Miguel-Cruz PA, Niño-Peña A, Batista-Marrero K, Miguel-Soca P. (2016). Factores de riesgo de cáncer bucal. Rev Cubana Estomatol. 2016; 53(3).

4. Anuario Estadístico de Salud 2017. MINSAP. Dirección de Registros Médicos y Estadísticas de Salud. La Habana, 2018. https://instituciones.sld.cu/cimeq/2018/04/11/anuario-estadistico-de-salud-2017/

5. Anuario Estadístico de Salud 2018. MINSAP. Dirección de Registros Médicos y Estadísticas de Salud. La Habana, 2019. https://instituciones.sld.cu/estomatologiascu/2019/04/30/publicado-el-anuario-estadistico-de-salud-2018/

6. Anuario Estadístico de Salud 2019. MINSAP. Dirección de Registros Médicos y Estadísticas de Salud. La Habana, 2020. https://salud.msp.gob.cu/disponible-edicion-48-del-anuario-estadistico-de-salud/

7. Anuario Estadístico de Salud 2022. MINSAP. Dirección de Registros Médicos y Estadísticas de Salud. La Habana, 2022. https://salud.msp.gob.cu/presentan-edicion-50-del-anuario-estadistico-de-salud/

8. Barrera-Cruz JT, Quenorán–Almeida VS. Experiencias del personal de enfermería en el manejo de quimioterapéuticos. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología 2022;2:233. https://doi.org/10.56294/saludcyt2022233.

9. Olazabal-Reyes D, Ocampo-Ricardo A, Ricardo-Díaz L. Intervención educativa sobre cáncer bucal en pacientes fumadores que acuden a consulta de Consejería. Alcides Pino, 2018-2019. Revista Estudiantil HolCien. 2021; 2(1).

10. Salazar-Martínez Y. Intervención comunitaria sobre lesiones premalignas y cáncer bucal en el consultorio 24. La Demajagua. 2017-2019. [Trabajo de terminación de especialidad en opción al título de Especialista de I Grado en Estomatología General Integral. Facultad de Ciencias Médicas de la Isla de la Juventud, Cuba, no publicada].

11. Matos-Arias SA. Intervención comunitaria sobre lesiones premalignas y cáncer bucal en el consultorio 1. Santa Fe. 2017-2019. [Trabajo de terminación de especialidad en opción al título de Especialista de I Grado en Estomatología General Integral. Facultad de Ciencias Médicas de la Isla de la Juventud, Cuba, no publicada].

12. Hernández-Álvarez D. Intervención comunitaria sobre lesiones premalignas y cáncer bucal en el consultorio 3. Nueva Gerona. 2017-2019. [Trabajo de terminación de especialidad en opción al título de Especialista de I Grado en Estomatología General Integral. Facultad de Ciencias Médicas de la Isla de la Juventud, Cuba, no publicada].

13. Vásquez Navarro JJ. Características clínicas e histopatológicas del cáncer oral según tiempo de exposición al factor de riesgo en pacientes del Hospital Hipólito Unanue durante los años 2014-2017. [Tesis para optar el grado de maestro en Odontología]. Universidad Nacional Daniel Alcides Carrión. (2019). http://repositorio.undac.edu.pe/handle/undac/1964

14. Rodríguez-García K, Montes-de-Oca-Carmenaty M, Chi-Rivas J, del-Todo-Pupo L, Berenguer-Gouarnaluses J, Lorenzo-Rodríguez M. Rotafolio para la promoción de conocimientos sobre el cáncer bucal. Universidad Médica Pinareña 2021; 17(3):725.

15. Reyes DJP, Ferrer RL, Castellanos MSR. Contribution of genetic factors in the occurrence of breast cancer in cuban women. Data and Metadata 2022; 1:37. https://doi.org/10.56294/dm202275.

16. Toledo-Pimentel BF, Cabañín-Recalde T, Machado-Rodríguez MC, Monteagudo-Benítez MV, Rojas-Flores C, González-Diaz ME. El empleo del autoexamen bucal como actividad educativa en estudiantes de Estomatología. Rev EDUMECENTRO 2014; 6(1):35-45.

17. Cajamarca EBG, Cevallos ERG, Gaona JSG, Ayala ADA. Conocimiento y factores asociados a la detección de cáncer de cuello uterino. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología 2022; 2:211-211. https://doi.org/10.56294/saludcyt2022211.

18. Vázquez-Carvajal L, Góngora-Ávila C, Frías-Pérez A, Pardo-Rodriguez B, Llerena-Piedra J. Intervención educativa sobre conocimiento de caries dental en escolares de sexto grado. Universidad Médica Pinareña 2021; 17(2):693.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

FUNDING

No financing.

DECLARATION OF AUTHORSHIP

Conceptualization: Rosa María Montano-Silva, Yanelilian Padín-Gámez, Yoneisy Abraham-Millán, Reinier Ruiz-Salazar.

Research: Rosa María Montano-Silva, Yanelilian Padín-Gámez, Yoneisy Abraham-Millán, Reinier Ruiz-Salazar, Ladisleny Leyva-Samuel, Douglas Crispín-Rodríguez.

Data curation: Rosa María Montano-Silva, Yanelilian Padín-Gámez, Yoneisy Abraham-Millán.

Formal analysis: Reinier Ruiz-Salazar, Ladisleny Leyva-Samuel, Douglas Crispín-Rodríguez.

Methodology: Rosa María Montano-Silva, Yoneisy Abraham-Millán.

Writing - original draft: Yanelilian Padín-Gámez, Ladisleny Leyva-Samuel, Douglas Crispín-Rodríguez.

Writing - proofreading and editing: Rosa María Montano-Silva, Reinier Ruiz-Salazar, Yoneisy Abraham-Millán.